Profile

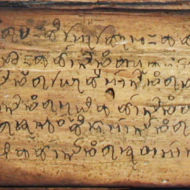

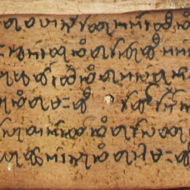

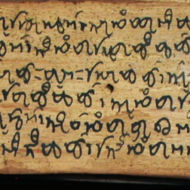

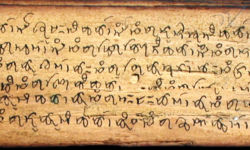

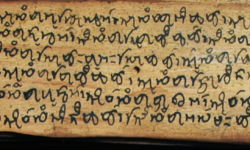

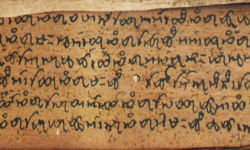

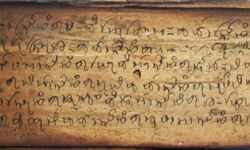

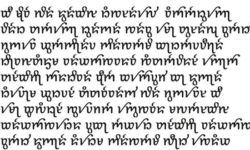

The Ahom (or Tai Ahom) script of Assam, India, is a sad illustration of how powerful a force colonialism can be in suppressing cultural individuality — but also that domestic forces such as caste or class warfare can be just as destructive in terms of cultural imperialism. The Ahom people originally came from Yunnan province in China, possibly around 1200. The earliest inscription in the Ahom script, on a stone pillar, dates from the 15th century. The alphabet also appears on coins, brass plates and numerous manuscripts on cloth or on the bark of the Sasi tree.

They ruled the Assam valley for six centuries, gradually converting from their own form of Buddhism to Hinduism, until their kingdom fell to the Burmese in 1819 and their ruling class was all but wiped out. The province was liberated by the British in 1825.

Once the British colonial forces occupied the region, though, a policy for taming the hostile tribes was immediately generated. The Ahom, the Assamese and other groups were lumped together and characterized as an “unattractive,” “degenerated” and “stupid people.” The insults were one thing; the grouping of different peoples with distinct cultures and histories was in many ways worse. Worst of all was the British attitude that they would deal with only high-class Hindus; anyone else (such as the Assamese, the Ahom, and other local peoples) was beyond the pale.

In order to try to shed themselves of this stigma, the Assamese tried to distance themselves from the Ahoms and assert their cultural superiority. Several new organizations were founded in the late nineteenth century such as the Assamese Language Improvement Society, the Assam History Society, and the Assam Literary Society in an effort to demonstrate that the Assamese were a cultured and civilized people, a Hindu people. When the Ahom protested, the Hindu community published a book called Ripunjay Smriti in which they defamed the Ahom as a polluted group and suggested they should perform rituals to cleanse themselves for seeking reentry into the Hindu caste fold. The harsh language of the Hindu Assamese left the Ahom with an unenviable choice: give up their historic identity and try to assimilate into Assamese society, or relinquish Hinduism, give up learning the Assamese language and return to local dialects and archaic rituals of ancestor worship. The same choice, in a more general sense, faces all minority and indigenous peoples even today.

By the end of the nineteenth century conventional thinking held that Ahom culture and language were either dead or were folded into Assamese to the point where there was no point in making a distinction. In 1931 the category “Ahom” was no longer even included in the census.

But Ahom was by no means dead.

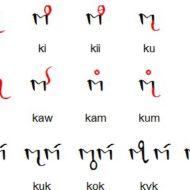

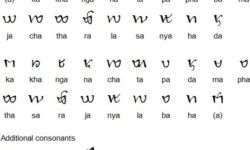

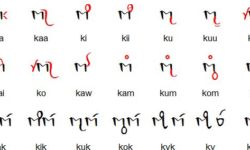

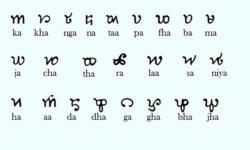

The first Ahom font was created in 1920 for an Ahom-Assamese-English dictionary, compiled by Golap Chandra Barua. Although the accuracy of the dictionary itself was subsequently called into question, the font was used in a number of other influential publications and has since become an authoritative model.

In 1967 the Ahom petitioned the Indian government to recognize them as a separate community “in which Ahom-Tais and the various other tribes would enjoy social recognition and all political rights.” The petition was turned down. Instead, the Ahom were forced to remain a sub-group of the Hindu Assamese — a “backward community.”

A turning point was the publication of Padmeshwar Gogoi’s Tai and the Tai Kingdoms with a Fuller Treatment of the Tai-Ahom Kingdom in the Brahmaputra Valley (1968), which gave the Ahom people a new name and a revived sense of historical legitimacy, not to mention a connection with the Tai people elsewhere in south and southeast Asia.

The new term Tai Ahom was seized upon and the new Tai-Ahoms revived a religion calling it Phra Lung, which emphasized the worship of ancestors, mainly heroic warriors.

“New prayers were written by the late Domboru Deodhai Phukan, the last of the Tai-Ahom ritual experts,” wrote Yasmin Saikia. “Domboru Deodhai explained to me the Phra Lung religion in these words. ‘Phra is a Buddha-like figure. Lung means the Sangha. Phra Lung means the community of the worshippers of Phra.’ Dietary habits were also changed to mark the departure from Hinduism. Beef, taboo among caste Hindus, was introduced in the Tai-Ahom diet, as did partaking of alcohol called haj or lau pani.”

As the century came to an end, a new Tai Language Academy was established at Patsako, new Tai festivals and commemorative events were created and publicly celebrated, and several conferences were organized in Assam and elsewhere. Recently the Tai Ahom International Society has continued these efforts.

Yet those identifying as Ahom continue to be among the poorest in Assam, which is one of the poorest states in India. The future of the Tai Ahom language, script and culture remain in the balance.

“I think very few people speak Tai Ahom,” said Mrinalinee Khanikar, a Tai Ahom living in northeast India. “It’s an endangered language. In upper Assam a few villages have kept it alive in Tinsukia, Sivasagar.” Sivasagar, formerly known as Rangpur, was the capital of the Ahom Kingdom from 1699 to 1788. “[Most of us] all speak [the] mainstream Assamese language.”

Yet she is far from turning her back on her cultural heritage.

“I am so proud of my rituals of the marriage ceremony, choklong, meaning ’round’ in Tai, when priests came from upper Assam and we celebrate a festival, mei-Dam-mephi, to offer respect to forefathers, with 101 earthen lamps beautifully decorated.

“I feel proud that we had such refined civilization where women had an equally important and powerful place in society. These are aspects I admire among Tai Ahoms as well as the skill of weaving silk and beautiful dresses.

“Tai Ahoms were a patrilineal society but women had an equally important role. They had a respectful position, and we never had to give dowry, unlike Indian society. Tai Ahoms were liberal. Women had freedom to choose, and it was the men who had to come and ask for girls. Women were regarded very highly in society, unlike in Indian society.

“I feel good that I belong to a much more civilized and refined culture and tradition.”

The Tai Ahom marriage system, called Choklong, may be unique in that, as part of the ceremony, the bride gives the groom a sword so he can protect her.

Updated August 2020

You can help support our research, education and advocacy work. Please consider making a donation today.

Links

General script, language, and culture resources

- Omniglot

- Wikipedia

- Unicode (PDF)

- Scriptsource

- Ahom Language Primer (PDF)

- A dissertation on Tai Ahom typeface design

- Tai Ahom International Society Video