Profile

“When I speak my own language, I am free. When I hear someone else speaking Rohingya, I feel like I am home.” —Rohingya refugee, via Translators Without Borders.The relationship between language, freedom, and home, is an especially poignant one for the Rohingya, who until 2016 were an ethnic Muslim minority in Myanmar numbering roughly one million.

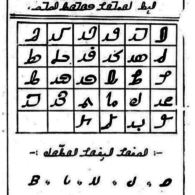

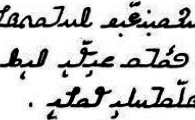

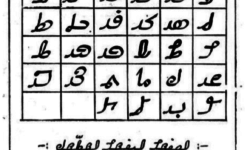

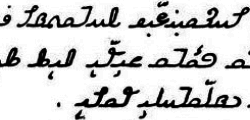

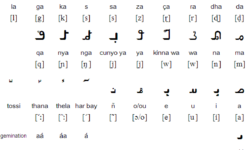

The Rohingya have their own culture, language and script. In the past, Rohingya has been written in the Latin, Arabic, Urdu and Burmese scripts, but in the 1980s, looking to creating a unique script that was their own and reflected their own culture, the Rohingya Language Committee completed that task under the guidance of Maulana Mohammed Hanif — hence the name “Hanifi.” Its Arabic flavor reflects the Rohingya religion and history — they say they are descendants of Arab traders and other groups who have been in the region for generations — and religion.

But the government of Myanmar, a predominantly Buddhist country, refused to grant the Rohingya citizenship, and as a result most of the group’s members have no legal documentation, effectively making them stateless. Myanmar’s 1948 citizenship law was already exclusionary, and the military junta, which seized power in 1962, introduced another law twenty years later that stripped the Rohingya of access to full citizenship. They were even excluded from the 2014 census, the government refusing to recognise them as a people and claiming they were illegal immigrants from Bangladesh.

Starting in late 2016, Myanmar’s armed forces and police started a major assault on Rohingya people in Rakhine State in the country’s northwestern region. Investigations by the United Nations found evidence the Burmese military had committed wide-scale human rights violations, including extrajudicial killings, gang rapes, arson and infanticide. The United Nations described the military offensive in Rakhine, which provoked the exodus, as a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing.”

Risking death by sea or on foot, some 700,000 Rohingya fled the destruction of their homes and persecution for neighbouring Bangladesh.

As with the Karen and Karenni people thirty years earlier, (see the Kayah Li profile) the surviving Rohingya found themselves in refugee camps, attempting to maintain a sense of dignity and community by preserving and teaching their language.

Mohammad Noor, creator of the Hanifi Rohingya font, reports that there are about 50 Rohingya community Schools in Bangladesh refugee camps teaching Rohingya Alphabet Hanifi script. “We are estimating over 25 thousand kids learning in these centres. In Malaysia and Saudi Arabia there about 2 thousand kids learning in different centres. We do also have a few centres in Burma. There are number of school syllabus, general books, magazines and many other types of content already developed and still developing more.”

You can help support our research, education and advocacy work. Please consider making a donation today.

Links

General Script, Language, and Culture Resources

- Omniglot

- Wikipedia

- Rohingya Academy Online Program

- Article on Rohingya Struggle

- Scriptsource

- Rohingya Language Book A-Z

- The Rohingya Language Academy

- The Rohingya Language Academy (YouTube)

- Rohingya at Archive.org