Profile

If we define writing as an organized series of visual symbols that represent the basic sounds of a language, the sona sand designs of the Lunda-Tchokwe group of the Bantu people in eastern Angola (plus northeast Zambia plus parts of the Democratic Republic of the Congo plus parts of the Republic of the Congo) push that definition so far it finds itself utterly out of its depth.Each design combines art, performance, narrative, and even mathematics in such a way that even to represent it as a stationary image robs it of its startling, delightful impact and meaning. Yet the sona may be part of a visual tradition over two thousand years old.

Paulus Gerdes writes: “The Tchokwe people (or Quiocos), with a population of about one million, predominantly inhabit the northeast of Angola, the Lunda region. Traditionally they are hunters, but since the middle of the 17th century they have dedicated themselves also to agriculture. The Tchokwe are well known for their beautiful decorative art, ranging from the ornamentation of plaited mats and baskets, iron work, ceramics, engraved calabash fruits and tattooings, to paintings on house walls and sand drawings.

“When the Tchokwe meet at their central village places or at their hunting camps, they are used, sitting around a fire or in the shadow of leafy trees, to spend their time in conversations that are illustrated by drawings (lusona, pl. sona) on the ground. Most of these drawings belong to a long tradition. They refer to proverbs, fables, games, riddles, animals, etc. and play an important role in the transmission of knowledge and wisdom from one generation to the next.”

“It was late March in 1921 when we arrived at the conjunction of the Kunjamba River with the Kuueyu River,” wrote Emil Pearson, a missionary who lived in the area for several decades and wrote about his experiences in his 1977 book People of the Aurora. He noted down more than a hundred Sona and their accompanying stories, calling them “sandgraphs.”

“During nearly half a century among the VaNgangela I found only four men who had real knowledge of them…. In making the sandgraphs, the loose sand and soil are scraped away with a stick or the side of a hand, leaving a smooth surface. Dots are then made with the fingertips in the proper patterns. The index finger and the ring finger are used simultaneously. After the first two dots have been made, the index finger is placed in the hollow made by the ring finger and the latter makes a third dot. This is repeated until the row is completed. Then the second row of dots is made in the same fashion, forming squares. When the number of dots required for the particular figure is complete, dots are then made in between the rows, the new dots being centers of diagonals. The first drawing of dots is called `Ku Sona,’ (to draw), while the in-between dotting is called `Ku Sononuena’ (to draw in between).

“When the dotting is completed, the real drawing begins. Using the index finger the artist draws the lines and curves with a sure hand and without hesitation until the figure is complete. The completed figure is called a `Kasona’ (plural, `Tusona’). As a rule, if the figure is fairly intricate, the drawing is made in silence. But, if it is simple, the tale is told as the drawing proceeds. The religious drawings are most fascinating,” he concludes with an admirable lack of dogma, “and are a lasting testimony to the prime religious beliefs of the African people.”

To call them “drawings,” though, undersells the element of performance. The akwa kuta sona — drawing expert — begins by cleaning and smoothing the sand or dust, and then uses his fingertips to create a matrix pattern of equidistant dots. (This pattern actually has a series of inherent algorithms that mathematicians and IT experts have explored with what can only be described as glee.) The dots may represent trees, features of the landscape, people, animals, or points along a journey.

He then begins his narrative, tracing a pattern that winds among and around the dots, never taking his fingers from the ground, never retracing the drawn path. Sometimes the pattern is symmetrical and predictable, sometimes not. The drawn line may represent a river, a fence, a wall, a journey, or even more intangible forms of connectivity, and sometimes the dots themselves are enlarged or altered, becoming characters in the story. The effect is spellbinding.

Perhaps you should just watch this video before reading on.

“The designs have to be executed smoothly and continuously,” Gerdes explains, “as any hesitation or stopping on the part of the drawer is interpreted by the audience as an imperfection and lack of knowledge, and assented to with an ironic smile.”

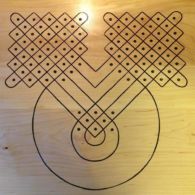

The most famous lusona is a creation narrative.

The figure at the top is God, at the left is the Sun, at the right is the Moon and at the bottom is a human. The lusona represents the path to God.

One day the Sun went to visit God. God gave the Sun a chicken and said, “Return in the morning before you leave.” In the morning the chicken crowed and woke the Sun. When the Sun went to God, God said, “You did not eat the chicken I gave you for supper. You may keep the chicken but return here every day.” That is why the Sun circles the earth and rises every morning.

The Moon also went to visit God and was given a chicken. In the morning the chicken crowed and woke the Moon. Again God said, “You did not eat the chicken I gave you for supper. You may keep the chicken but return here every twenty-eight days.” That is why the Moon cycle is twenty-eight days long.

The human also went to visit God and was given a chicken. But the human was hungry after such a long journey and ate part of the chicken for supper. The next morning the Sun was already high in the sky when the human awoke, ate the rest of the chicken, and hurried to see God. God said, “I did not hear the chicken crow this morning.” The human replied fearfully, “I was very hungry and ate it.” “That is all right,” said God, “but listen: you know that the Sun and Moon have been here, but neither of them killed the chicken I gave them. That is why they themselves will never die. But you killed yours, and so you must die as it did. But at your death you must return here.”

And so it is.

You can watch this story unfold, albeit with a ghastly computer-generated voice narrative, by visiting the Links tab.

Under the influence of colonialism, according to ethnologist Gerhard Kubik, the sona tradition has been vanishing: “What we find today is probably only the remnant, becoming more and more obsolete, of a once amazingly rich and varied repertoire of symbols.”

Vanuatu also has a critically-endangered tradition of sand storytelling. We’ll add more information as soon as it becomes available.

Postscript:

When I first started looking through sona designs, I made the mistake of thinking of them as mandalas, and seeing a kinship with the kolam or rangoli patterns of South Asia. Actually, I was making two mistakes: the first was to think of sona as being mainly decorative (or perhaps, like kolam, meditative); the second was to think of them only in terms of the finished product.

In my defence, I had been misled by the sources that described them as “designs” or “patterns” or “drawings,” and by internet searches that showed only the finished product, so it was perhaps understandable to think of sona the way we think of “finished” art—the painting of the wealthy burgher’s wife or of the nighthawks in the diner, the act of painting completed, the subject frozen in time. Done. Ready to show us, and for us to be impressed.

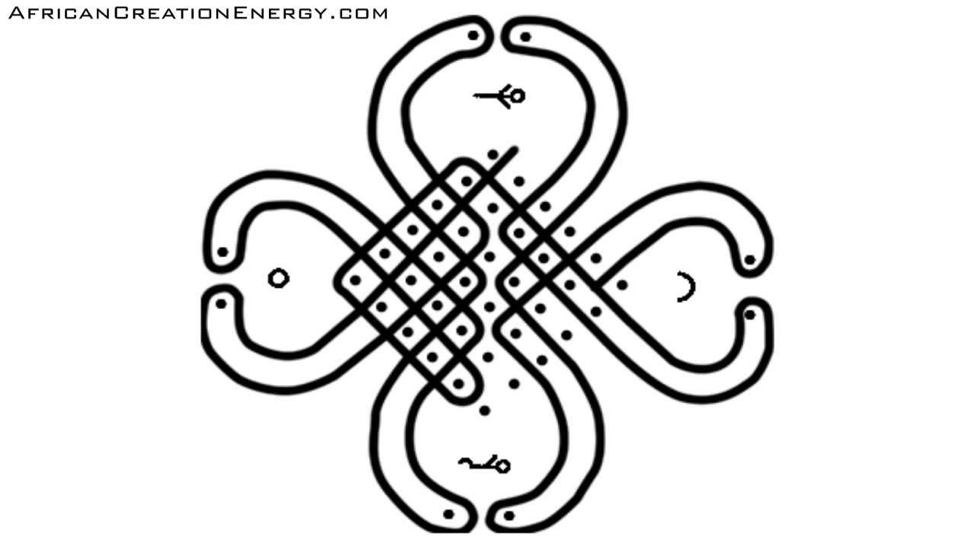

Everything changed when I saw the lusona “Casa de homem com duas mulheres” — house of a man with two women.

(As I found it on Pinterest, the natural habitat of Internet theft, it’s hard to be sure of the source, but I think it’s from Mario Fontinha’s Desenhos na Areia dos Quiocos do Nordeste de Angola.)

For the first time, I saw the lines as movements, and the entire lusona not as a design but as a drama.

In the Tchokwe narrative, perhaps the two women were two wives, or a wife and a mother-in-law. For me, seeing in my my own experience, they were a father, a daughter, and the father’s new wife, the daughter’s stepmother.

I took the two women to be the two large cluster of dots, upper left and upper right; the man is the smaller cluster below and between. Crucially, there are no horizontal lines between the women — they do not deal with each other directly, but through the man. If we follow the lines, one of the women comes to the man and tells him one thing; the implication I read is “Do something about this!” He goes to the other woman, but the narrative just comes back to him again, over and over. He is powerless; nobody is satisfied; the pattern never ends.

The circles in the lower portion could represent the house, I suppose, but to me they represented his head, where everything goes around and around, and he can’t stop thinking about how he can find a resolution or broker a peace, how to deal with this endless stalemate.

You can help support our research, education and advocacy work. Please consider making a donation today.

Links

General script, language, and culture resources

- Wikipedia (Chokwe Lusona)

- Wikipedia (Chokwe Language)

- Wikipedia (Chokwe People)

- Omniglot

- Chokwe Art

- History and culture written in sand

- Sona geometry

- Chokwe art and life

- Tribal African art

- Creation story sona (YouTube)