Profile

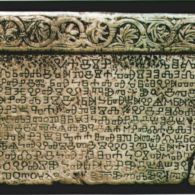

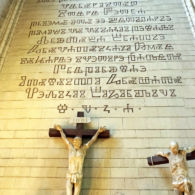

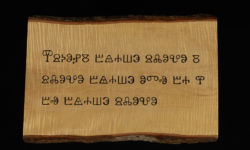

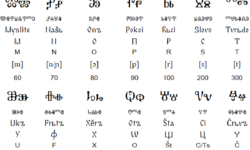

Here and there in Central and Eastern Europe (for example, in the Cathedral of the Assumption in Zagreb), the visitor can see, carved into the walls of churches and cathedrals, fascinating panels of mysterious writing, ornate and yet apparently as old as stone itself. That writing is in Europe’s only endangered alphabet: Glagolitic.The oldest known Slavic alphabet, Glagolitic was probably created in the 9th century by Saint Cyril, a Byzantine monk from Thessaloniki. He and his brother, Saint Methodius, were sent by the Byzantine Emperor Michael III in 863 to spread Christianity among the West Slavs in the area.

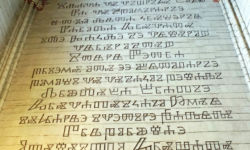

The Slavs already had scripts of their own, but the missionaries dismissed them as “mere dots and lines.” The brothers decided to translate liturgical books into the Old Slavic language that was understandable to the general population, but as the words of that language could not be easily written by using either the Greek or Latin alphabets, Cyril decided to invent a new script, called Glagolitic (possibly from the Croatian word glagolitse, meaning “writing”).

Not long afterwards, followers of Cyril and Methodius developed a second liturgical alphabet, named Cyrillic in Cyril’s honor, possibly incorporating some features of the Glagolitic script.

As the centuries passed the Cyrillic script, which was more flexible and frankly easier to write, became used more and more, and Glagolitic began a long slow fade. As the second millennium drew to a close, Cyrillic had ironically become the totemic script of the godless Soviet Union, but the only people who still read and wrote Glagolitic were priests, and when they died (don Marko Cvitanović on Pašman in 1977, don Vinko Rasol on Silba in 1965), day-to-day usage of Glagolitic disappeared.

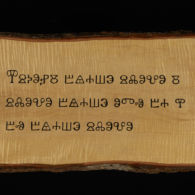

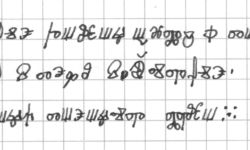

Yet the script somehow refused to die. Over the years Glagolitic sightings came in from Eastern Europe like reports of a bird thought to be extinct. Someone remembered seeing Glagolitic on postcards and, in 1994, on the 5-kuna coin commemorating the 500th Anniversary of the Senj Glagolitic Missal. Occasionally, the Glagolitic Mass is revived, sung in Old Church Slavonic. University courses still studied the script, and a scholar from Dubrovnik at a medieval conference mentioned that the Glagolitic alphabet was being taught in local schools as part of the national heritage. Another mentioned seeing tattoo artists inking in Glagolitic.

A third recalled a conference on the island of Krk when a group of children, who regularly attended afternoon courses on Glagolitic, presented the concertgoers with clay tablets with Glagolitic letters incised on them, to be worn on a string around the neck.

“The group was about 25 strong, all participated in the course in their spare time and seemed to be very enthusiastic,” he wrote, adding wistfully: “Whether that school still exists I do not know.”

Glagolitic had moved to the position of many ancient scripts (such as runic alphabets, or Ogham in Ireland): the fact that it is not readily read and understood makes it all the more mysterious, fascinating and alluring.

So much so, in fact, that between 1977 and 1985 the sculptor Janeš Želimir created a series of giant Glagolitic letters along the road between Roč and Hum in Croatia, and other Glagolitic letter parks have sprung up since.

And perhaps that is the best way to view Glagolitic: visually striking, sculptural, culturally emblematic rather than functional, larger than life.

You can help support our research, education and advocacy work. Please consider making a donation today.

Links

General Script, Language, and Culture Resources

- Omniglot

- Wikipedia

- Unicode (PDF)

- Introductory Video to Glagolitic

- Croatian Glagolitic Heritage

- Background to Glagolitic Alphabet

- Scriptsource

- List of Glagolitic Books

- List of Glagolitic Manuscripts

- National Library of Russia

- Baska Glagolitic Path Article

- A Glagolitic-numeral kids’ quiz show

- A Glagolitic Christmas

- Croatian Glagolitic Script