Profile

The Yezidi script has a long history, a long period of dormancy, and recent evidence of some revival.

On its website, the Spiritual Council of the Yezidis in Georgia describes the Yezidis as an “ethno-confessional group,” numbering around a million, most living in their historic homeland in Iraq, with others in Syria, Turkey, Armenia and Georgia. For centuries, they have existed as a closed religious community, apart from other Kurds, suffering occasional persecution by members of the other religions of the region.

The roots of Yezidism go back to the ancient cults of the Middle East. Yezidis believe in one God (Khude) and three of his hypostases (Tausi Malak, Ezid, and Shikhadi). According to the Yezidi sacred texts, in the twelfth century, God revealed himself in the face of the preacher Sheikh Adi Musafir. Yezidis respect all other religions, and show deference to the prophets of different religions. Yezidis do not proselytize: it is believed that the Yezidi religion cannot be adopted, one can only be born into it.

The native language of the Yezidis is Kurmanji (also called Northern Kurdish), in which there is a rich religious poetry in the form of sacred texts that form the basis of the Yezidi religion.

Two such texts are the oldest surviving manuscripts in the Yezidi script, written sometime in the twelfth or thirteenth centuries on sheets of thin parchment made from processed gazelle leather: Maṣḥaf Raš and Ktébī Jalwe.

The first book contains a monologue of Tawûsê Melek, the principal angel in the Yezidi religion. In Maṣḥaf Raš, cosmogony is described, which reaches beyond traditional Yezidi views. To complicate matters, the Yezidi clergy have concluded that although there were, in fact, Yezidi sacred manuscripts known as Maṣḥaf Raš and Ktébī Jalwe, the versions that survived were corrupted copies, so they have the remarkable quality of being respected and preserved as examples of the Yezidi script, but not as a source of the Yezidi faith.

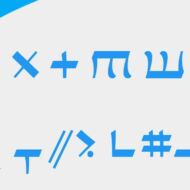

Between the creation of Maṣḥaf Raš and Ktébī Jalwe and the twenty-first century, the Yezidi script declined and fell almost entirely out of use. In 2013, the Spiritual Council of Yezidis in Georgia decided to revive the Yezidi script and use it to write prayers, sacred books, on the organization letterhead, and in the Yezidi heraldry. For this purpose, two orientalists and specialists, Kêrîm Amoêv and Dimitri Pirbari, modernized the Yezidi alphabet and adapted it to the phonetic features of the modern Yezidi language.

Today the Yezidi script is used by clergymen in the Yezidi temple in Tbilisi. On the walls of the temple, the names of saints are also written in this alphabet. A book of prayers Dua’yêd Êzdiyan in the Yezidi script has been published recently. Even so, it is not clear how widely the script is used today, even within the Yezidi religious community. A positive sign may be that the script was adopted into Unicode in 2020, though it is not yet supported by Windows.

You can help support our research, education and advocacy work. Please consider making a donation today.