One sign of the importance of writing in the spread of religion—and vice versa—can be seen in the phrase “People of the Book,” an early term of respect for members of faiths that had written scriptures.

It may also be the only script ever to have been created to write a language no longer in everyday use.

Zoroastrianism is one of the world’s oldest continuously-practiced religions. Possibly as much as 3,500 years old and traditionally based on the teachings of Zoroaster (or Zarathustra), Zoroastrianism was the state religion of the Persian Empires for more than a thousand years, from around 600 BCE until the Muslim conquest.

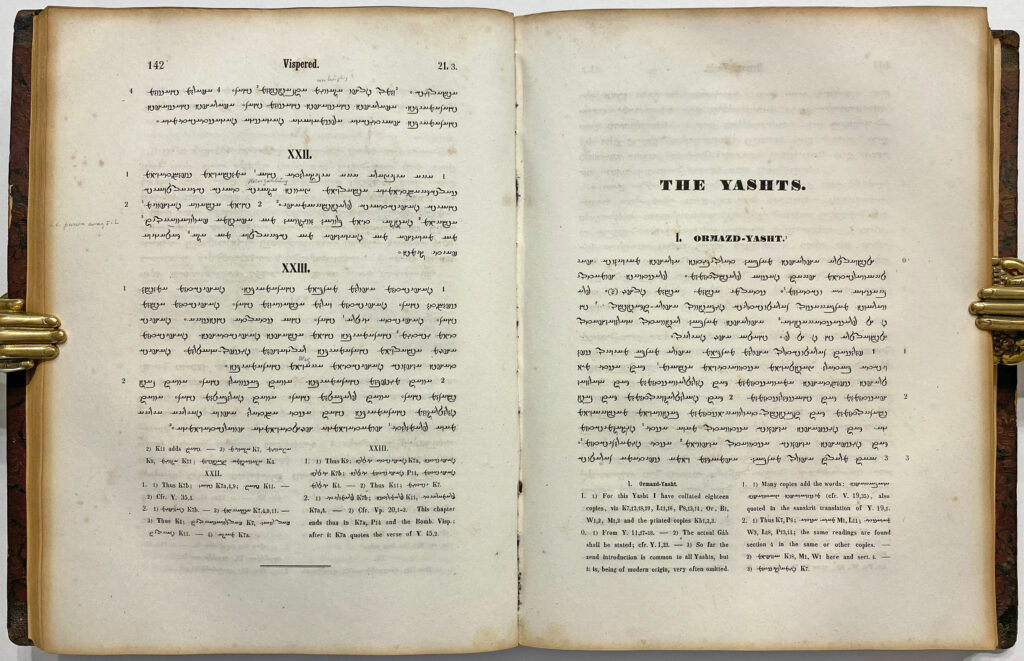

The language used in the early practice of Zoroastrianism was Old and Young Avestan, actually a pair of related regional Indo-Iranian languages. This pair of languages have so completely died out, though, that all we know of it/them is what survived in Zoroastrian liturgical use. This hyper-narrowing led to a remarkable situation in which this pair of languages were named backwards: the Avesta is the primary collection of religious texts of Zoroastrianism, so the languages have come to be called Avestan—even though they were functionally extinct, in a daily-use sense, by the time the Avestan texts were written!

The development of the Avestan alphabet, starting around the fifth or sixth century CE, may have been the result of the religion’s desire to compete with Buddhists, Christians, and Manicheans, each of which were, in their own ways and before the Islamic phrase had been coined, people of the book. The Zoroastrian religion, until that point, had been based on oral tradition—a recitation of prayers in specific cadence and inflection, passed down from teacher-priests to their pupils, accompanied by rituals in which a text would have been an encumbrance and a distraction. A phonetic written form would allow for a greater exactness of pronunciation, and a more coherent body of wisdom.

The right-to-left script devised to write the Avesta ultimately consisted of 53 characters—the majority derived from Pahlavi which, in turn was derived ultimately from Aramaic, some seemingly adapted from Greek, and a few invented specifically for the purpose. It was a full alphabet, with characters for vowels and came with a unique system of punctuation.

All languages and scripts associated with religions, however, are both protected and vulnerable as the fortunes of the religion rise and fall, and Avestan, being functionally extinct outside the Zoroastrian setting, was especially vulnerable.

Once the Sasanian Empire had fallen to the Arabs by 651 CE, Zoroastrianism began to decline. It survived mainly in what nowadays may seem an unusual context: India.

Over the next several centuries, many Persian Zoroastrians decided to escape persecution and preserve their religious traditions by fleeing eastwards into Sindh and Gujarat, where they were known as Parsis, meaning “Persians.” They were granted permission to stay by the local ruler, Jadi Rana, on the condition that they adopt the local language, Gujarati, and that their women adopt local dress, the sari.

The Parsis developed a substantial Zoroastrian community in India, especially in Gujarat, and many of the religion’s surviving documents originate in India. But the everyday language of the community steadily changed—to Gujarati with Sindhi, Marathi, Hindi, Bengali or other regional languages used for trade and mercantile reasons and interacting with domestic help. Many of the ancient texts were preserved in translation, especially into Persian and Gujarati, using the Persian and Gujarati scripts.

From the 19th century onward, the Parsis gained a reputation for their education and widespread influence in all aspects of society. They played an instrumental role in the economic development of the region over many decades; several of the best-known business conglomerates of India such as the Godrej and Tata groups are run by Parsi-Zoroastrians.

At the request of the government of Tajikistan, UNESCO declared 2003 a year to celebrate the “3000th anniversary of Zoroastrian culture,” and in 2011 it was announced that for the first time in the history of modern Iran and of the modern Zoroastrian communities worldwide, women had been ordained in Iran and North America as mobedyars, or assistant clergy, authorized to perform the lower-rung religious functions and initiate people into the religion, though this step is highly contentious, largely supported by the Iranian Zoroastrians but not the vast majority of Parsis.

Today the world population of Zoroastrians is perhaps a little more than 100,000 (with the greatest population center being around Mumbai, with smaller groups elsewhere in the region, and the world), and is shrinking.

Yet even though the Avestan script remains at the core of Zoroastrian worship, it has become curiously asemic: only scholars and priests can read it, and for the devout faithful it survives as a series of symbols with spiritual weight rather than literal meaning or phonetic value, representing a language that died more than 2,000 years ago.

19.0760° N, 72.8777° E

5/1/6

a:a