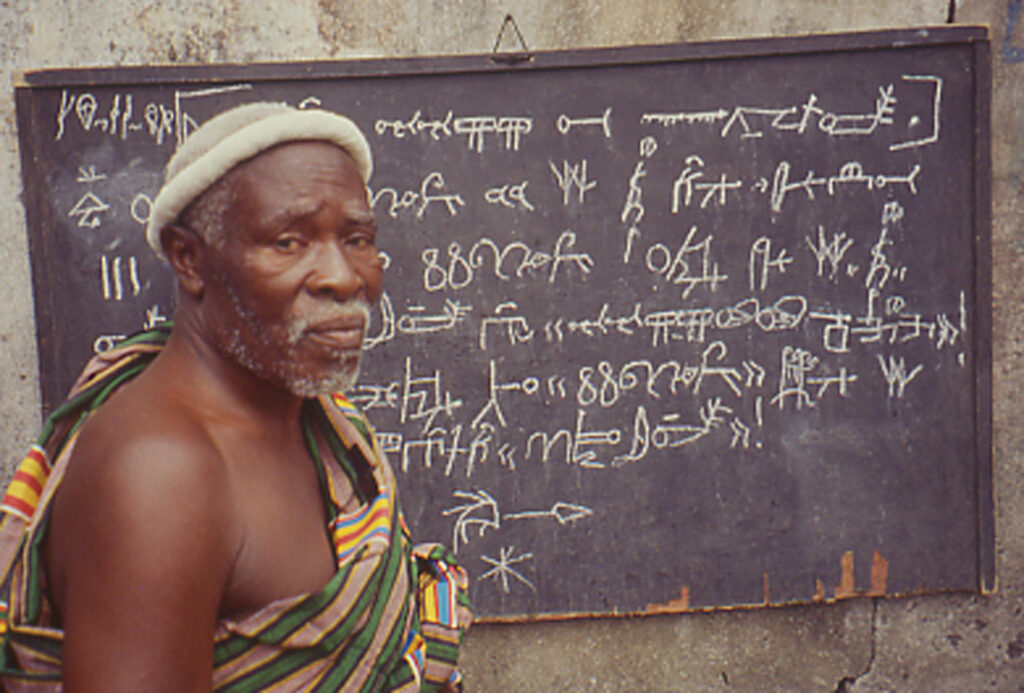

The Bété syllabary was revealed on March 11, 1948, when, Frédéric Bruly Bouabré explained later in life, “the heavens opened before my eyes and seven colourful suns described a circle of beauty around their Mother-Sun, I became Cheik Nadro: ‘The one who does not forget.’”

What Bouabré, an artist from Côte d’Ivoire, felt called to remember was nothing less than the sum of the knowledge and understanding of the world in general and his people, the Bété, in particular.

As if that were not enough of a challenge, he invented a unique alphabet for the purpose– 448 monosyllabic pictograms, an inventory of sounds that would allow to transcribe all the languages in the world, based on geometric designs he found on a series of small red and white stones that he concluded were part of an ancient, lost Ivoirean alphabet.

This was a radical act in many ways. Although between 600,000 and 3 million Bétés live in the Côte d’Ivoire, the language has no official status and all education is conducted in French.

In keeping with the sub-Saharan African tradition of forging alliances between writing and art, in the 1970s, Bouabré started to transfer his thoughts to hundreds of small drawings in postcard format, using a ballpoint pen and colour pencils. These drawings, gathered under the title of Connaissance du Monde, form an encyclopedia of universal knowledge and experience. For Bouabré, his drawings are a representation of everything that is revealed or concealed — signs, divine thoughts, dreams, myths, the sciences, traditions. Frédéric Bruly Bouabré’s original drawings are held in the Pigozzi Collection of Contemporary African Art in Geneva.

The Bété script was exhibited in the Tate Modern, London, as part of their ‘Poetry and Dream’ display in February 2011. “Bouabre is himself a kind of builder of encyclopaedias because his personal work consists in inventing a specific African alphabet,” the Ivorian curator and art critic Yacouba Konate told the BBC. “He thinks it’s easier for an African to learn, to get new knowledge, when he works inside an African writing system, an African language.”

Bouabré died in 2014 at the age of 89. The Bété syllabary is still not taught in schools and has no official status, but a small number of Bouabré’s former students in Zepreguhé, led by his son Olivier Tagro, continue to try to bring it to active life.

We would love to hear from anyone who knows more about the progress of these revival efforts.

6.9000° N, 6.3667° W