“Traditional sources tell us that the written word first came to Tibet in the form of indecipherable treasures,” writes Patrick Dowd, “the material manifestation of a promise that would wait five generations to be fulfilled. In the year 233, as the twenty-eighth Tibetan king Lhatotori Nyentsen sat on the rooftop of his palace, several objects descended from the sky, carried on a beam of sunlight. The first was a silver choten, a symbolic representation of the Buddha’s mind. The other was a chest containing three Buddhist scriptures. As the books came to rest on the roof, a voice resounded from above, proclaiming, `In five generations’ time, there will arise a king who will understand the meaning of these objects.’

“The king recognized these miraculous manifestations as holy relics but, as no one in the whole of Tibet was literate, their meaning remained impenetrable, hidden while plainly present. He, therefore, named them the `secret antidotes’: `secret’ because their ultimate significance was unknown, and `antidote’ because even the illiterate, non-Buddhist king intuited that these blessed artifacts could cure the suffering of sentient beings. For later generations of Tibetans, the appearance of the secret antidotes was believed to be the fulfillment of a prophecy made more than seven hundred years earlier by the Buddha, who declared that, in the future, objects would descend from the heavens as a harbinger of his sacred dharma coming to the `land of snows.’”

This is much more than a quaint fable: it illustrates how clearly Tibetan culture has understood the importance of writing, and of its own script—an importance underlined by the fact that until the Chinese invasion of 1950, official Tibetan currency dated from the year 233, when writing, recognized as of profound spiritual importance even before it was recognized and used as writing, arrived on the palace roof.

A second narrative, somewhat more earthly but still spiritual in purpose, concern the origins of the Tibetan script itself.

Songtsen Gampo, who assumed the throne in 618, was the first great emperor of Tibet, beginning an imperial expansion that would come to include the entire Tibetan plateau and areas of what are now Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Nepal, Bhutan, and China–more than 4.6 million square kilometers, an area nearly the size of the Roman Empire at its peak. More lastingly, Songtsen Gampo laid the foundations for a Buddhist culture that continues to this day.

The Buddha had explicitly insisted on the importance of writing:

At the end of five hundred years,

my presence will be in the form of letters.

Consider them as identical to me

and show them due respect.

Songtsen Gampo, the story goes, summoned sixteen wise ministers to his court and charged them with an epic quest to travel south, learn the languages of India, and distill from them a script for the Tibetan language.

“The mission was catastrophic,” writes Dowd, “resulting in the deaths of nearly all of the ministers.… Some of the ministers were devoured by tigers or murdered by thieves. Others drowned while crossing rivers swollen with monsoon rains. Still others contracted malaria or similar tropical diseases, dying fetal and prostrate on the ground, soiled and drenched in sweat. Only one minister prevailed: Tonmi of Anu.”

Tonmi made his way down to South India, nearly 1,500 miles from Lhasa, where he found Brahman Lijinkara and asked the guru to teach him to write.

Brahman Lijinkara replied, “I know twenty different writing systems. Which one would you like to study, child of Tibet?”

(A quick aside here. It’s a Western weakness that we think in terms of single scripts, and try to get the world to learn just one—ours. Most people, especially in Asia, South Asia, regularly use more than one. India may have had twenty scripts in Brahman Lijinkara’s day, but now it has well over a hundred.)

“For the next seven years,” Dowd continues, “Tonmi diligently learned the twenty different Indian writing systems, all of which were carved on a pillar on the shore of a lake at the guru’s home. Brahman Lijinkara also taught his pupil the sciences of grammar, lexicography, poetry, literature, and philosophy, but only after he had perfected the various scripts. The letters of these twenty scripts were the foundation on which the mansion of language and the palaces of all other learning could be built.

“Having mastered these writing systems, Tonmi created a new script, one that a thirteenth-century Tibetan scholar and poet would describe as `golden letters arrayed like stars and planets.’ In Tonmi’s script, the fifty letters of Sanskrit were refined to thirty consonants, seven signs that could be attached to their tops and bottoms, and four vowels. All letters were assigned gender, with the consonants generally classified as masculine and given the title of `clarifiers’ while the vowels were classified as feminine and called `melodies.’ When joined together, they represented a union.”

These origin stories are vitally important for two reasons, one short-term, one long-term, both concerning the profound relationship between a culture and its traditional script.

“The script is closely linked to a broad ethnic Tibetan identity,” writes Wikipedia, “spanning across areas in India, Nepal, Bhutan and Tibet.”

But of course there is no longer an independent, autonomous country called Tibet, at least according to the Chinese government. So the Tibetan script gives us a case study in the value, meaning, health and uses of a script when (as has happened throughout history) one culture overruns another.

As Patrick Dowd’s story illustrates, the Tibetan script (which even has three different forms for different purposes) has immeasurable spiritual and historical meaning for Tibetans, and because of the influence of Tibet throughout the region, well beyond Tibetan borders.

One manifestation of this deep meaning is that even though the spoken Tibetan language has changed in a number of ways over the past thousand years, the script, which was critical for the dissemination of early Buddhism, has remained the same

To those who think of writing as merely a toolkit for representing speech, it would seem as though the script and spelling should be reformed and modernized. However, if you see your script as golden letters like stars and planets, and the work of someone who had journeyed from Lhasa to southern India in the face of death by tiger, modernization seems more than somewhat heretical.

Moreover, to quote Wikipedia again as the writer dances around awkward political realities, “However, modern Buddhist elites in the Indian subcontinent insisted the classical orthography should not be altered even when used for lay purposes.”

If we rewrite “modern Buddhist elites in the Indian subcontinent” as “the Tibetan government in exile and the Dalai Lama, living in Dharamshala,” everything becomes clear. The Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1950 (including the subsequent deaths of hundreds of thousands of Tibetans and the destruction of some 6,000 monasteries) made the Tibetan script a visible symbol of Tibetan identity, an identity more than 1,500 years old but now under threat.

Under Chinese dominance, both the Tibetan language and script have been more or less severely controlled, depending on current policy. The Cultural Revolution led to widespread death and destruction, especially of Buddhist manuscripts in Tibetan. More recently, a subtler form of control has been characterized by the Chinese government as the promotion of bilingual education.

As is in the case of the Mongolian people in the autonomous region of Inner Mongolia, “bilingual education” is a weighted term—specially, weighted against mother-tongue education in both spoken and written language.

Human Rights Watch reported in 2020 that since the 1960s, Chinese has been the language of instruction in nearly all middle and high schools in the region, where nearly half of Tibetans live, but practices introduced over the last decade by the regional government are leading more primary schools and even kindergartens to use Chinese as the teaching language for Tibetan students.

China formally introduced a policy of “bilingual education” in 2010 for schools in all minority areas in China, but schools are increasingly staffed by non-Tibetan-speaking teachers, have virtually no Tibetan textbooks and have isolated the use of Tibetan to Tibetan-language classes.

“Ordinary Tibetans have expressed widespread concern about the increasing loss of fluency in Tibetan among the younger generation as a result of changing school policies. While many favor Tibetan children learning both languages, there is considerable opposition to Chinese authorities’ approach, which erodes the Tibetan language skills of children and forces them to consume political ideology and ideas largely contrary to those of their parents and community.”

According to the Guardian, China’s constitution maintains that all ethnicities in China “have the freedom to use and develop their own spoken and written languages.” Yet when language-rights campaigner Tashi Wangchuk complained about the lack of Tibetan-language teaching in his area, he was sentenced to five years in prison, the court said he was guilty of “inciting separatism” and regional police in China declared that campaigning on mother-tongue issues was illegal, and a form of “underworld gang crime.”

Minority Tibetan languages are effectively excluded from all public domains, and Free Tibet reported that on 1 September 2021, the Chinese government replaced all school textbooks in Tibet with Chinese language teaching materials while the Chinese language has been established as the official medium of instruction in schools at every level from kindergarten to high school.

“Chinese authorities have also cut off a number of alternative ways for Tibetan children to learn their mother tongue. Authorities have forcefully shut down Tibetan language schools and private schools where the Tibetan languages were being taught and forbidden Tibetan parents from organising online coaching classes for their children during their summer and winter holidays, a key restriction since most parents prefer to give tuition on Tibetan language and Buddhism during this time. Monasteries are also being forced to teach Buddhism in the Chinese language.”

Is Tibetan an endangered alphabet, then, if it is still used throughout the region, still used for the practices of Tibetan Buddhism around the world, (it is the official national script for Bhutan, for example, where it is used to write Dzongkha, the national language) and still used to a diminished degree in Tibet, or the Autonomous Province of Tibet?

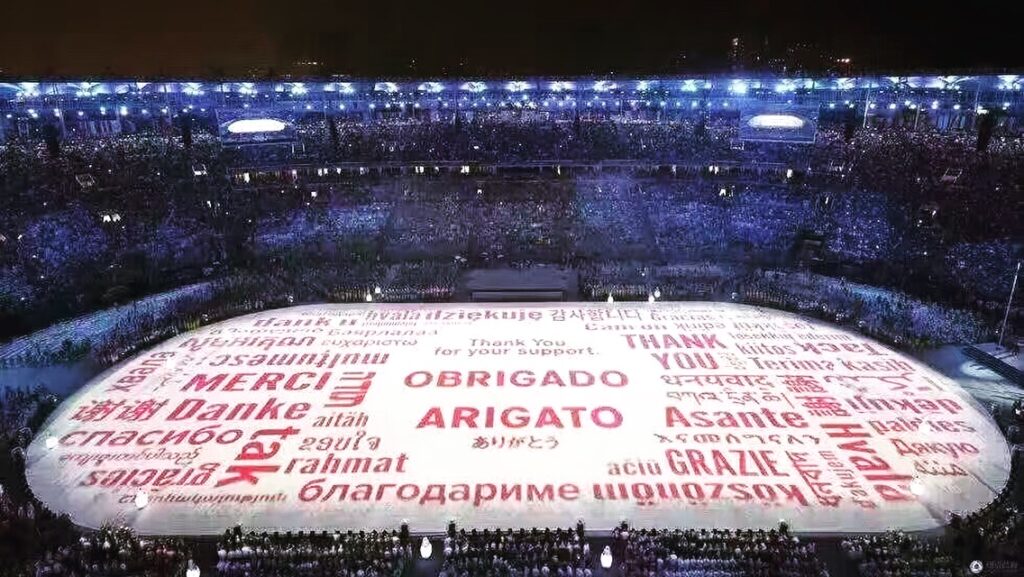

When the Tibetan writer Woeser saw the words “Thank you” projected in Tibetan script at the closing of the 2016 Rio Olympics, she was delighted, but recognized what a complex and contradictory situation it illustrated.

On the one hand, the script could be said to have represented Bhutan rather than Tibet, as Bhutan uses the same script. Some pointed out a paradox: why should people who don’t actually use the Tibetan script at home become overjoyed and even proud, when seeing some Tibetan appear in a foreign place?

“You suddenly realize that for one, you no longer have a presence, your presence has been taken away; second, you also no longer have a future; in the future, not even your mother tongue belongs to you, it belongs to someone else and so your future has also been taken away. So the only thing you have left is the past.”

She quotes an online friend: “It doesn’t matter why this Tibetan script appeared or which country they represent, these letters are definitely found in Tibetan language and Tibetans subjectively saw themselves reflected in these symbols; when one sees one culture being trampled down everywhere, this feeling of blind and spontaneous affection is really like a luxury….”

29.6526° N, 91.1378° E